|

2/26/2024 Abuse in SportsAttention to readers: The below article discusses various types of abuse in sport. The article provides an overview of recent cases that include discussion of: child abuse, sexual abuse, hazing, psychological abuse, and other forms of illicit behaviour. Descriptions or details of any individual examples of sexual abuse have not been included, though some general examples of what might constitute as physical or phycological abuse, are included. Resources: · The End Sexual Violence NL’s 24/7 Support and Information Line is available at 1-800-726-2743.

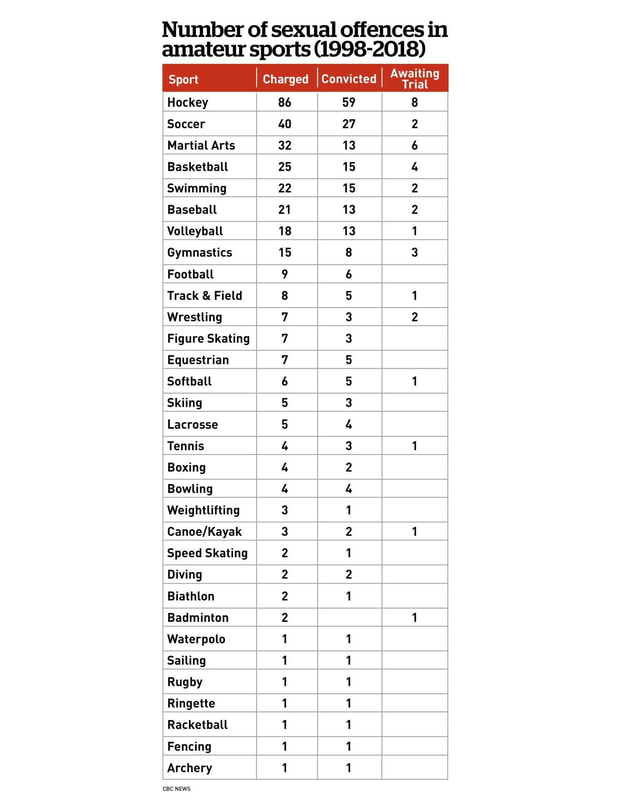

Abuse in Sports: Empowering Survivors "It's amazing how you can experience a very emotional trauma and not even think about it. And then something as simple as reading a paper and reading about somebody else's abuse can trigger all of these emotions and imagery and just it's so vivid — you're right back in it.” That is how Mr. Daniel Carcillo, former NHL player, and 2-time Stanley Cup champion, described the abuse he endured while playing as a rookie in the Ontario Hockey League. Mr. Carcillo is one of the representative plaintiffs in a proposed class action lawsuit, commenced in 2020, against 60 amateur hockey teams, the Western Hockey League ("WHL"), the Ontario Hockey League ("OHL"), the Quebec Major Junior Hockey League ("QMJHL"), and the Canadian Hockey League ("CHL"). In their submissions the Plaintiffs[i] describe a systematic, longstanding history of abuse with in the CHL, explaining a “cruel, toxic culture”[ii] that “pollinated across the Leagues as players and coaches moved between teams and as players of one generation became coaches of the next.”[iii] Detailing the abuse, the Plaintiffs submitted that “from coast to coast, young players were physically, sexually and psychologically abused on team buses, in locker rooms, and at team sanctioned ‘rookie parties’ […] Many rituals involve sexual and physical torture. Shrouded in an enduring culture of silence, the abuse became an open secret.”[iv] Perhaps most chilling is the Plaintiff’s submissions[v] detailing of how those in charge of governance of the league had ample, repetitive evidence of the “systemic, enduring abuse”[vi] yet those in charge continued to argue that the abuse was “isolated and non-systematic”- discrediting third party reviews experts, burying their reports which said otherwise.[vii] Another legal action connecting hockey players and abuse has also been in the headlines recently, with police investigations into a sexual assault involving five former members of the 2018 Canadian world junior team. In 2022 a Plaintiff, under a pseudonym, brought a civil action against eight unnamed players, Hockey Canada, and the Canadian Hockey League concerning a sexual assault which occurred in 2018. The case ultimately settled out of court, however, has been cited as the catalyst of a significant public conversation regarding the abuse that is occurring within organizations like Hockey Canada, and how such abuse is enabled to continue. Not Just Hockey While front of mind for many due to the recent stories in the news, abuse in sport is not limited to hockey. As federal Minister of Sport and Physical Activity Carla Qualtrough recently said, “there is a sports safety crisis in our country.” It doesn’t take much digging to find examples of this ‘safety crisis’ in sports, particularly when it comes to sexual abuse. An analysis by CBC published in 2019 found that coaches in 36 different sports had been convicted of sexual offenses in Canada within the past 20 years: Figure 1 Coaches convicted of sexual offenses (from CBC News)

Types of abuse While recent cases and, therefore, related public discussion has focused on abuse with a sexual element, all forms abuse are wrongs that can permeate harm well past the initial infraction: The mental health consequences of violence and abuse are devastating, long-lasting and, according to Reardon et al., in sport can be associated with reduced performance and achievement, early exit from sport, reduced self-esteem, body image disturbances, disordered eating and eating disorders, substance use disorders, depression, anxiety, self-harm and suicide. In addition, the propensity to cheat and dope is increased in the context of violence in competitive sports; furthermore, childhood psychological abuse correlates with long-term, complex post-traumatic and dissociative symptoms. Violence and abuse in sport affect the victims and their athletic environment, as well as the victims' personal and social relationships, even outside of sport. Source. Physical or psychological abuse can be so ingrained in the culture of sports that sometimes participants don’t even really understand, in the moment, how damaging it can be. They might feel they don’t have any power to report the abuse. Sometimes, even understanding where the harm originates can feel confusing: how do you complain about hazing or bullying if the coach is encouraging of both? Or how do you sound the alarm if many teammates are suffering from the same sort of abuse, but seem to take it all with a laugh or general deference? The “team-first mentality”- a sense of “you’re in or you’re out” - are factors that can contribute to silent suffering.[i] An implicit promise of ostracization if you do speak out or question things permits an assurance of compliance for abusers and those perpetrating the harm.[ii] Physical abuse, despite the damaging effects, is sometimes harder for some players to separate from the broader sport culture. Many types of sports involve physical components with other players- checking in hockey, tackling in rugby, pinning in wrestling – but every physical interaction with a player isn’t, generally, what the discourse is referring to when discussing ‘abuse in sports.’ Sports players, generally, have an ‘implied consent’ to some level of physical play- usually that which a reasonable person would contemplate as being appropriate within the game. As a recent case in Ontario described: a “player’s implicit consent is not unlimited. A player does not accept the risk of injury from conduct that is malicious, out of ordinary, or beyond the bounds of fair play.”[iii] There are many types of abuse being perpetrated in sports which is not, and cannot be, accepted or ‘consented’ to. Physical abuse, accordingly, certainly exists.[iv] Psychological abuse, despite being the most common type of abuse in sports, can feel to some players inherent to the ‘high stress’ nature of sports. Repetitive cruel comments, demeaning insults, and discriminatory practices can feel, to an individual, hard to nail down as specifically harmful, even when they are ‘above and beyond’ the ‘normal’ razzing. When someone is ‘cruel’ at times, but also jubilant when things are going right, it can be easier to convince oneself that the harm was not real in the first place. As discussed by David Gilbourne and Mark Anderson in Critical Essays in Applied Sport Psychology: The athletes' reports in the study described a sport environment pervaded by an unpredictable and volatile emotional cycle of reward and punishment. In the closed context of a competitive sport team, this cyclical repetition of fear and reprieve and punishment and reward can result in a feeling of extreme dependence on the (perceived) omnipotent perpetrator (Herman, 1997). As one female athlete who was sexually abused by her coach said, “To us at that time, his word was like gospel.” From the psychology literature, we understand this state as a traumatized attachment to the perpetrator. Under these conditions, disclosure simply does not happen. Silencing is an integral—not separate—part of the experience, and these aspects of the perpetrator's methodology target the individual's emotional life as a method of keeping that person in a state of confusion, fear, and entrapment. Types of Abuse and the Law In civil law, there are a number of ‘causes of action’ that come to mind when considering possible harms in sports, particularly with reflection to the harms discussed in case law and the news:

Abuse In Sport Is Widespread and Does Not Differentiate On ‘Level of Play’ While it may feel that many of the cases being discussed in the media concern ‘professional’ athletes, or high-performing athletes, that does not mean abuse isn’t happening on the local scale. Former federal Minister of Sports, Pascale St-Onge, when discussing federal jurisdiction for improving ‘safe sport’ said that: "[t]he vast majority of cases of abuse and maltreatment happen outside the federal scope […] [t]hey happen in local clubs, leagues and gyms, all of which are within the responsibility of provincial, territorial and local authority.” In 2019 CBC News and Sports released a three-part story, finding that: At least 222 coaches who were involved in amateur sports in Canada have been convicted of sexual offences in the past 20 years involving more than 600 victims under the age of 18, a joint investigation by CBC News and Sports reveals. And the cases of another 34 accused coaches are currently before the courts. In February 2023 CBC reported that another “83 coaches have been charged or convinced across multiple sports, provinces and jurisdictions.” Research also speaks to the prevalence of abuse in sport, a research study published in 2022 finding that: “studies indicated that psychological abuse is most frequently reported by athletes, with 38–72% of athletes reporting at least one experience, followed by sexual abuse (9–30% of athletes) and physical abuse (11–21% of athletes).”[viii] Abuse in Sports and the Public Discourse – How Public Discussion Can Elicit Personal Memories and Reconsiderations As the former NHL player, Mr. Carcillo, aptly put it, hearing about abuse through the news can often spark reflection on one’s own experiences. This phenomenon has been proven by researchers. Regarding high-profile sexual harassment (SH) cases in the USA, a group of researchers found that “a substantial number of people had the potential to have their memories of SH be triggered by high-profile media stories of sexual misconduct. Specifically, those who read media about SH or sexual misconduct were reminded of and reinterpreted previous SH experiences, which in turn positively impacted (i.e. increased) self-reports of SH experiences.”[ix] Whether abuse happened just a few weeks ago, or many years in the past, people experience reconsideration of their memories and experiences when hearing about other’s stories in the news. To be clear: any ‘delay’ in recognition of past abuse is not reflective of the level of harm of that abuse, or it’s effects. Just because it may take someone some time to be able to consciously affirm that they had been harmed, does not negate the reality of that harm The publicity around stories of abuse and calls to action will likely continue as societally, we are still in a process of fully identifying the problem, and contemplating how to fix it. While this continues, to those who have survived abuse, such continual coverage can be terrifying, and often debilitating. It means an indeterminate period of time in which one can be inodiated with frequent reminders of the abuse they endured. Who’s To Be Held Accountable? And how? When large news stories like the ones we are now seeing pop up, after processing the information, we go through a process of contemplating next steps. Societally we are trying to find out how to make right what has happened, while ensuring that changes are made so no such harm will occur again. As a complex issue, abuse in sports cannot be properly addressed by one measure alone. And those who have been harmed may seek different recourses. Below are some potential options survivors might choose, but many more may be available. The Office of the Sport Integrity Commissioner takes complaints about sport organizations who are signatories of the Abuse-Free Sport program. More details available: https://sportintegritycommissioner.ca/process/overview There have also been calls for an inquiry into abuse in sports. Inquiries serve a number of functions: they empower investigations, allowing for public oversight, etc. Their findings, however, are not binding. Determinations of wrongdoing are not determinations in liability or guilt. On an individual level, survivors of abuse have a few different recourses. Including pursuing criminal and/or civil matters. For further details on reporting abuse to the police, the Journey Project has a helpful guide (though angled, specifically, to reports concerning sexual violence): https://journeyproject.ca/reporting-police/. Pursing Compensation and Justice In civil matters, survivors would be looking at commencing an action, sometimes referred to as a ‘lawsuit’ in pursuit of compensation for damages they incurred as a result of the abuse. In civil law we look to damages, often in the form of financial compensation, “to place him or her in the same position as he or she would have been in had the tort [wrongdoing] not been committed.”[x] Though monetary sums cannot erase the harm, and it can feel abstract, especially at the beginning, for survivors to imagine that a ‘value’ can be calculated to compare to what they’ve endured- a competent lawyer can guide and empower survivors through the process. They can seek compensation for the damage that’s occurred, and for any future or ongoing care that may be required as a result of the harm. Limitation Periods – Newfoundland and Labrador In the context of civil actions, considering the laws of Newfoundland and Labrador as they presently stand, misconduct of a sexual nature can be, in situations outlined by the Limitations Act, without a limitation period.[xi] How the law considers ‘misconduct of a sexual nature’ may be broader than you think, and if you're unsure about how the law would treat what you've experienced, the best thing to do is consult with a lawyer who can place your experience in the context of the law and advise you as to your options. For other types of abuse, there can be limitation periods of around 2 years[xii], with some potential flexibility when looking at ‘discoverability’ or some actions in equity. However, even if the type of harm falls into the 2-year limitation period, if the abuse happened while someone was a child (under the age of 19)[xiii] they generally have until two years after reaching adulthood (as in, until the age of 21) to commence a civil action. Pseudonym for lawsuit Even though we're talking about widespread news reports and athletes who have chosen to proceed using their real names, that level of notoriety is not a necessary consequence of commencing a lawsuit- survivors can also proceed by use of pseudonym. Survivors of childhood and/or sexual abuse are often worried about the stigma, or an unwanted exposure of their lives and experiences. They feel like they aren’t able to consider legal action because they don’t want their name and details of what happened to them open to the public. At Budden and Associates we work with survivors at every stage of the process, and believe in empowering and supporting clients in considering the options available to them. As an example, for survivors of childhood and/or sexual abuse, a first step we often take, upon the choice of the client, is to apply to the court to protect anonymity. In practice, this means we often apply for a pseudonym application when commencing an action. A pseudonym order protects the name of the survivor, and any identifying information, ensuring such identifying information cannot be reported or shared outside the necessity of the court process. The general procedure of this application has been detailed by Allison Conway in a prior blog post: https://www.buddenlaw.com/our-blog/reducing-harm-to-survivors-in-the-civil-process Empowering Survivors News about abuse in sports is likely to remain in the news cycle for a while. And as the news continues, more and more people may begin recognizing abuse in their own past. As discussed above, there are a number of options available for survivors to consider- all of them with advantages and disadvantages. What path a survivor takes- including deciding to not pursue the matter- is a highly personal decision. There is no correct answer, there is no path that is better than another - the best decision is the one that the survivor feels is best for them. However, if a survivor wants to discuss their options, we are here. We know how hard it is to make that initial contact. We meet clients where they are- with consultations in person, over the phone, or via video chat, and can provide accommodations if you would like to bring a support person. You will not be expected to share every detail in our first meeting, or come in with any specific plan - we will do our best to provide an outline of what options are available. And there is never a requirement for you to pursue something after meeting with us. We can provide a free consultation to those who may want to discuss their options. Simply give us a call (709-576-0077) or email ([email protected] or [email protected]) to arrange. [i] The class is defined as "all former and current players who claim to have suffered the ‘abuse’ while playing in the CHL League between May 8, 1975 and the present.” Where abuse is defined as “physical, and sexual assault, hazing, bullying, physical and verbal harassment, sexual harassment, forced consumption of alcohol and illicit drugs, and the use of homophobic, sexualized and/or racist slurs directed against minors playing in the Leagues.” See: Statement of Claim, paragraph 1 [ii]kmlaw.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Factum-Plaintiffs-O3-Oct-2022.pdf at para 3 [iii] Ibid [iv] Ibid at para 4 [v] The proposed class action is still proceeding through the courts, so there has not been any finding of facts of these claims. [vi] Ibid at paras 5-6 [vii] Ibid [viii] See: Critical Essays in Applied Sport Psychology by David Gilbourne & Mark Andersen, finding “This variable [“embedded psychological abuse”] may be particularly salient in the environment of competitive sport, as research has documented apparently normalized coaching and instructional practices and team initiation rituals that constitute psychologically abusive practices (Brackenridge, Rivers, Gough, & Llewellyn, 2006; Kirby & Wintrup, 2002; Leahy, 2001). It may also specifically relate to the particular strategies that appear to be used by perpetrators in athletes' environments.” [ix] Ibid which further found “From the psychological literature, we know that the repeated imposition of a powerful perpetrator's world view, and the lack (due to isolating and silencing strategies) of alternative reference points, can entrap the victim within the perpetrator's viewpoint (Herman, 1997).” [x] Casterton v. MacIsaac, 2019 ONSC 190 [xi] Mountjoy M, Brackenridge C, Arrington M, et al International Olympic Committee consensus statement: harassment and abuse (non-accidental violence) in sport British Journal of Sports Medicine 2016;50:1019-1029. [xii] Philip H. Osborne, The Law of Torts at 456. [xiii] Ibid at 275. [xiv] Prinzo v. Baycrest Centre for Geriatric Care, 2002 CanLII 45005 (ON CA) [xv] Willson E, Kerr G, Battaglia A, Stirling A. Listening to Athletes' Voices: National Team Athletes' Perspectives on Advancing Safe Sport in Canada. Front Sports Act Living. 2022 Mar 30;4:840221. doi: 10.3389/fspor.2022.840221. PMID: 35434612; PMCID: PMC9005768. [xvi] Amber, B., Dinh, T.K., Lewis, A.N., Trujillo, L.D. and Stockdale, M.S. (2020), "High-profile sexual misconduct media triggers sex harassment recall and reinterpretation", Equality, Diversity and Inclusion, Vol. 39 No. 1, pp. 68-86. https://doi.org/10.1108/EDI-12-2018-0222 [xvii] Ratych v. Bloomer, [1990] 1 S.C.R. 940 at para 71 [xviii] Limitations Act, SNL 1995, C L-16.1 ss. 8(2) and 15(3)(c). [xix] Ibid at s. 5. [xx] Ibid at s. 15(5)(a) Comments are closed.

|

The content provided on this website is intended to provide information on Budden & Associates, our lawyers and recent developments in the law. Articles, blog posts, comments and other information on our website are not intended to be legal advice, may not be up to date and do not create a lawyer-client relationship between you and Budden & Associates. If you require legal advice, please consult with one of our lawyers directly.